As this year’s drought deepened and spread across the United States, many cities and farms took steps to cope. Bans on landscape irrigation conserved municipal supplies. Farmers pumped more groundwater for their crops to make up for the lack of rain.

But what’s a river to do?

Most rivers are last in line for help during dry spells. Their flows disappear, their fish go belly up, and their riverside habitats for birds and wildlife dry out and wither.

Although droughts are natural, and rivers have adapted to them, what’s unnatural is the extensive damming and diverting of their flows to satisfy growing human needs for drinking water, irrigation, energy production, and flood control. Those are important benefits, to be sure, but the flow alteration causes ecological harm even in wet years. When a drought strikes, rivers – and the life they sustain – often take a terrible hit.

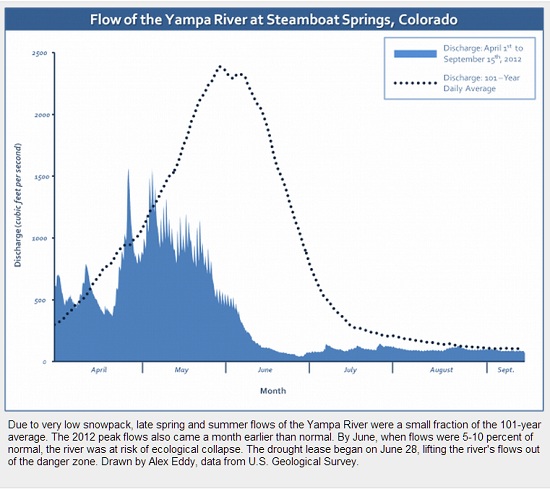

By late spring, a bad summer seemed to be in store for the Yampa River in the upper Colorado River Basin. The Yampa flows 250 miles (400 kilometers) across a storied valley of farms and ranches in northwestern Colorado, through the popular tourist town of Steamboat Springs, and west to Dinosaur National Monument, where it joins the Green River near the Utah border. On May 1, the snowpack that feeds the Yampa’s flow was 17 percent of average; by June 1 it was 6 percent.

“We were preparing for a devastatingly poor summer,” said Peter Van De Carr, owner of Backdoor Sports, situated on the banks of the Yampa in the heart of Steamboat.

The river’s flows dropped throughout the month of June. On Tuesday the 19th, it ran at 85 cubic feet per second (cfs), a key benchmark for local businesses because many recreational activities on the river are curtailed when flows drop below that level.

Van De Carr, who outfits customers with kayaks and tubes, saw dollars draining out of his cash register.

By June 27, the river’s flow had dropped to 40 cfs, just 5 percent of normal for that day of the year. Van de Carr and others worried about a repeat of 2002, the last severe drought in the region, when the Yampa dropped to 17 cfs, killing fish that couldn’t get enough oxygen or food, slamming local businesses at the height of summer tourist season, and generally decimating the ecosystem and the economy that depends on it.

That summer of 2002, the river “smelled like rotting seaweed,” Van De Carr recalled. “It was a nightmare.”

A Water Lease to the Rescue

But 2012 would turn out differently. On Friday, June 29, as if by a miracle, the river started to rise. By 9:30 that night, it was flowing at 71 cfs.

Something had happened that had never happened before in Colorado: an intervention to spare a river – and its dependents – from decimation during a drought.

Back in the spring, when the skimpy mountain snowpack spelled disaster for so many of Colorado’s rivers and streams, the non-profit Colorado Water Trust (CWT) issued a statewide request for water. Anyone willing to sell or temporarily lease water was encouraged to contact the CWT. If the water could help a river weather the drought, the CWT would consider buying it.

One answer to the call came from Kevin McBride, director of the Upper Yampa Water Conservancy District in Steamboat Springs. McBride had just had a contract with a customer fall through, leaving 4,000 acre-feet (1.3 billion gallons) of Yampa River water unclaimed in Stagecoach Reservoir. For the right price, McBride was willing to lease that water to the Colorado Water Trust.

“We rocketed that (project) to the top of our priorities,” said Amy Beatie, Executive Director of the water trust, based in Denver.

“It looked like a system that was ecologically going to crash,” Beatie said. “The river was starting to crater.”

So for a total of $140,000, or $35 per acre-foot, CWT leased the water district’s spare water. McBride had set the price, based on what he knew his board would approve. In that part of the West, the cost was very reasonable.

On June 28, the leased water began flowing out of Stagecoach Reservoir into the Yampa. The extra flow would directly benefit seven crucial miles downstream of the reservoir, as well as the river’s course through Steamboat and beyond. The idea was to keep the river as healthy as possible through the summer, by releasing about 26 cfs a day into September.

Along the way, the leased water provided multiple benefits. It generated extra hydropower at the Stagecoach Reservoir. It provided aesthetic and recreation benefits in Steamboat, helping businesses like Backdoor Sports avoid tens of thousands of dollars in lost revenues. Further downstream of the reach targeted for the lease, some irrigators even got more water for their crops, a welcome boost during a drought and dire economic times.

“The purpose of the lease is to maximize the beneficial use of water in Colorado,” Beatie explained. “These incidental benefits make this a win-win-win-win. “

Besides rescuing a river and its dependents, the Yampa drought-lease set a precedent in Colorado. It was the first use of a 2003 state law, passed in part in response to the devastating 2002 drought, that allows farmers, ranchers, water districts or other entities to temporarily loan water to rivers and streams in times of need.

“I think everyone was happy,” McBride said. “I didn’t know of any real opposition. And the river certainly benefited.”

Down to the River

Billy Atkinson, an aquatic biologist with Colorado Parks and Wildlife, dips his equipment into the river, and measures its temperature and dissolved oxygen. These are the river’s vitals, and Atkinson has been monitoring them all summer long.

It’s now August 21. I’m tagging along with Atkinson on his daily routine with a team from National Geographic’s Freshwater Initiative. Along with its partner, the Bonneville Environmental Foundation, National Geographic has contributed funds to the Colorado Water Trust to help pay for the water lease. We’ve come to the Yampa to see and document what the lease is accomplishing – and what disasters it may have helped avoid.

Atkinson has been worried in particular about the native mountain whitefish, a close cousin of salmon and trout that is found in only two Colorado river basins, the Yampa and the White. The whitefish population had declined alarmingly in the late nineties and, according to Atkinson, “really took a hit” in 2002.

When flows dropped so terribly low that year, Atkinson and other scientists witnessed that as the river warmed and filled with oxygen-robbing vegetation, the whitefish all gathered where the water was two degrees cooler, often in deeper pools behind rocks. The fish used their limited energy to pump oxygen over their gills, leaving little for feeding and other activities. All hanging out in one place, they also competed for space and aquatic insects, which also declined in numbers due to the warmer, poor-quality water.

All in all, 2002 was a tough time for the native whitefish. The main reason recreational tubing and kayaking are banned on the river when its flow drops below 85 cfs is to avoid further stressing the fish.

Atkinson also maintains and monitors a popular recreational, catch-and-release trout fishery. It is not uncommon to see fly fisherman in the waters at dusk, dawn and even mid-day, casting their reels into the Yampa’s babbling riffles.

Thanks in part to July rains but also to the water lease, conditions for the fish this year are a “tremendous improvement” over 2002, Atkinson said. The higher flows provide deeper, cooler water, which means more habitat, better oxygen levels and less predation pressure.

The drought lease “helped out significantly,” Atkinson said.

The next morning, we headed to Carpenter Ranch, about 20 miles downstream from Steamboat Springs. A pair of sandhill cranes peck in the fields for breakfast, their low staccato trumpet sounds filling the dawn air. Perched high above the river, a juvenile bald eagle spies the river below, looking for a bite.

Here, adjacent to the Yampa, is a working ranch leased out by The Nature Conservancy that is also a sanctuary for birds and wildlife that call the river home. Geoff Blakeslee, who started managing the ranch in 1996, is now the Conservancy’s Yampa River project director.

“The Yampa is the lifeblood of this valley,” Blakeslee said.

It’s also ecologically unique and valuable, with four endangered fish species and a globally rare plant community. The narrow-leaf cottonwood, box elder and red-osier dogwood that thrive along the Yampa’s banks typically don’t exist together. This rare plant assemblage is critical habitat for numerous animals, including more than 150 bird species that rely on it during migration. They also nest and raise their young there.

By keeping flows above harmful levels, the lease also helped sustain this unique ecosystem and its many dependents.

Lee Curby, a young farmer who leases land at Carpenter Ranch, was also grateful for the leased water. Earlier in the summer, before the lease went into action, Curby liquidated his herd of cattle because he feared not having a harvest sufficient to feed them. Because Curby’s land was far downstream from the river reach targeted by the lease, and Carpenter Ranch owned senior water rights on the Yampa, the lease allowed Curby to divert enough water for a late-season harvest of hay.

“(We) irrigated just in time to get a crop,” Curby said.

All in all, the water lease looks like a win-win. Or, as CWT’s Amy Beatie would say, “a win, win, win, win.”

From early July through September 15, the Yampa stream gage at Steamboat never registered less than 70 cfs. While welcome July rains added measurably to the river’s flow, there’s no question that the drought lease staved off what might have been a disaster for the river and the town it runs through.

With climate scientists warning that the dice are loaded for more droughts in the western United States, innovative approaches like this water lease can help ensure that rivers, and the aquatic life and businesses that depend on them, survive the dry times.

Since it was structured as a one-year lease, there’s no guarantee that the Yampa will fare as well the next time a drought hits. But this year’s success – and the multiple benefits it yielded – provides ample reason to develop similarly innovative schemes for the Yampa and other rivers in the future.

After all, for rivers that give so much to us, it only feels right to give something back in times of need.

National Geographic

Sandra Postel

Original article