Friends of the Yampa and American Rivers organized a trip down Colorado’s Yampa River in early June, to raise awareness about the last wild river in the Colorado River Basin. This post includes all four parts of a four-part series about the trip.

Day 1

Warm sun, blue sky, and white puffy clouds. Tall cottonwoods and western bluebirds. A brown river sliding by our packed yellow rafts, tied up at the Deerlodge put-in.

We’re going on a river trip.

This is the Yampa, one of the Colorado Basin’s, and the nation’s, last wild rivers. American Rivers named the Colorado River the #1 Most Endangered River in the country in April, and protecting the Yampa is one important puzzle piece for ensuring a healthier Colorado Basin in the long-term. The purpose of this five-day trip is to bring leaders together to explore the value of the wild Yampa and discuss the river’s future.

(See “How the Yampa River, and its Dependents, Survived the Drought of 2012“)

There are 20 of us – decision-makers, local officials, conservation advocates, scientists, and journalists. The trip was organized by Friends of the Yampa and American Rivers, and is supported by world-class outfitter OARS.

The Yampa River flows 250 miles through Northwest Colorado’s farms and ranches, and towns including Steamboat Springs, before joining the Green at Echo Park. While most rivers in the Colorado River Basin have been dammed and diverted for water supply and hydropower, the Yampa remains wild and healthy – an example of what rivers in this region were meant to be. There is a dam on the upper Yampa but it is far enough upstream that the river’s natural flows and functions are essentially intact.

We have lunch in the shade of the cottonwoods and look at a map of the river, spread out in the grass. Pat Tierney, who has floated the Yampa for 33 years in a row and is a professor at San Francisco State University, gives us a lesson in geology, pointing out locations of the Weber and Morgan formations. This river flows through a mind-boggling expanse of time. The canyon walls tell a story that is millions of years old.

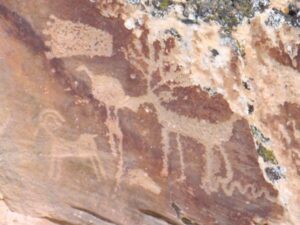

The Yampa winds through Dinosaur National Monument, home to the fossils of dinosaurs like stegosaurus and allosaurus. And just walking the riverbank it’s easy to find small marine fossils, hundreds of millions of years old. Adding to the layers and layers of time are the Fremont petroglyphs and pictographs, the Ute archeological sites along the river, and the initials of homesteaders, fur traders, and outlaws inscribed on the canyon walls.

Bruce, our guide from OARS, gives the whitewater safety talk and then it’s time to get on the water. We start downriver, leaving the open sky of the put-in and soon the ancient walls rise up and we’re in the canyon.

In the evening we camp at Teepee Hole and swim, cooling off in the hot sun. After dinner we sit in a circle around the campfire. As it gets dark and the stars come out, we talk about our work and our connections to the river.

I am five months pregnant, and in the midst of our discussion about consumptive and non-consumptive water use, instream flows and biological opinions, I feel the baby kick just as a shooting star arcs over the canyon wall. It’s one of those almost too-perfect moments wild rivers are full of.

Over the next several days we’ll dig into the science and economics and the policies that shape how the river is managed. And wrapped up around all of that will be our experiences, both shared and personal, that make this river real, alive, and part of us.

Why protect the wild Yampa? For me, on this first night, the reasons and moments are already piling up.

Day 2

Rivers move much more than water. One of their primary jobs is to move sediment – from giant boulders to cobbles, gravel, sand, and silt. This is how they sculpt landscapes and carve canyons, building habitat like beaches, sand bars, and back channels for fish, birds, and wildlife.

We eat lunch today on a cobble bar where it’s hard to count the many colors and shades of stone – from pinks and reds and purples to yellows, browns, and grays.

The river is running a little over 4,000 cubic feet per second– a typical level for this time of year. But last year, flows were so low (just 5 percent of normal in June) that the river’s water quality, fish and wildlife, and recreation were threatened. Fortunately, the Colorado Water Trust brokered a water lease during the critical summer months to restore flows, protecting fish and the recreation economy.

At the other end of the spectrum, 2011 was a big high-water year, with the river reaching 19,000 cfs during spring runoff. A lot of the beaches we’re seeing were built up by those floodwaters.

So those are two important values of a wild Yampa – its ability to transport sand and silt, and its peak flows that build a rich, dynamic ecosystem.

Pat Tierney is Professor and Chair of Recreation, Parks and Tourism at San Fransico State University. And he knows the Yampa better than most, having floated the river 33 years in a row. He sums it up, stating, “In a wild river system, all of the benefits are provided for free.”

When we dam a river we take away those benefits because the sediment clogs up behind the dam. Dams also often shave the peaks off of floods, “flatlining” the river’s flows. So protecting the Yampa in its wild state – preventing any new dam construction – is important.

Charlie Preston-Townsend, a Friends of the Yampa board member, explains that with most other rivers in the Colorado Basin already dammed and diverted, the Yampa provides a “control” – a reminder of what these rivers were, what they should be, and what they could be again.

In the afternoon we hike up Bull Canyon to Wagon Wheel Point. It’s hot and dry, and the shady spots in the lush side canyon feel good. At Wagon Wheel, 5,000 feet above the river, we peer over the edge and watch the swallows swoop up to eye level then back down again.

The rapids upstream of our camp look like little crinkles and a line of rafts are tiny specks on the water.

When it comes to rivers, we’re programmed to think cold and clear water is best. And while that’s true in some places, here on the Yampa warm and muddy is the way it should be.

All life here, from the cottonwoods to the pikeminnow, has evolved with the river’s rhythms.

The brown river winding far below is the heartbeat of these canyons. And that’s why we are here – to figure out how to keep it that way.

Day 3

Camped on the beach at Harding Hole, I’m in my sleeping bag under an old cottonwood tree. The birds wake me up at first light. We’ve seen so much wildlife on this trip so far, from western bluebirds, yellow warblers, and ravens to bighorn sheep, beaver, snakes, and scorpions.

The wild Yampa is an oasis for these animals in the desert. It’s also one of the last places in the Colorado Basin where we can find rare native fish like the Colorado pikeminnow. This fish evolved over thousands of years, adapting to the unique conditions of heavy sediment and seasonal high and low flows. Dams and reservoirs on the Green and Colorado rivers have eliminated much of the native fish habitat, so we’re lucky to have the Yampa.

Eric Kuhn, general manager of the Colorado River District, describes what happened to the habitat in the basin by comparing the river to a house: “Now all they have is half a bathroom and a couple of closets.”

We float for a while in the morning, then pull over on a large cobble bar near one of the few documented pikeminnow spawning sites.

We gather around Pat Tierney for a talk about native fish. He tells us pikeminnow could grow up to 70 pounds, and that it was once dubbed the Colorado white salmon – drawing the connection to the Pacific salmon I’m more familiar with, where I live in Oregon.

Like Pacific salmon, pikeminnow migrate. They can travel down the Little Snake River to the Yampa and back, more than 150 miles. Pat describes pikeminnow as part deep sea creature (because they live in the dark, naturally silty water) and part grizzly bear, because of their predatory nature. Truly a unique and remarkable fish.

What’s the value of a wild Yampa? For fish, the river is a lifeline. The Yampa may be our best chance to save species that are thousands of years old, from being lost forever.

Continuing downstream, we pass pictographs on the canyon wall, 800 years old. They are trapezoidal figures with arms raised. Every year they watch 5,000 to 7,000 rafters and kayakers float by – the Yampa is one of the most sought-after whitewater boating permits in the country.

In the afternoon we run Warm Springs rapid, the biggest of the trip. We’re lucky to have George Wendt, the owner of OARS, with us. He tells us how he witnessed the formation of this rapid during a flash flood in 1965.

This past winter there was a small landslide that further changed the rapid.

We get out to scout and watch the two other groups ahead of us run the rapid. Nobody has any trouble avoiding the big holes. When it’s our turn, we crash through the big waves and pull out safely in the eddy below, cheering as we watch the other rafts come down.

We camp at Box Elder and set up games of horseshoes and glow in the dark bocce. We swim to cool off and eat chips and salsa barefoot in the sand.

There are many ways to answer the question, “what’s the value of a wild Yampa?” This afternoon, it’s about fun.

Day 4

Today, we float the remainder of the Yampa to where it joins the Green River at Echo Park. It’s a short stretch of mostly flat water and we decide to have a quiet float, no talking, to appreciate the river sounds and soak in our surroundings.

We listen to the birds and the breeze. The gentle creak of the oars, the dip and drip of the wooden blades in the water, the rub of a rubber sandal sole on a raft tube. The sunny canyon cliffs and ledges slide by.

Soon, Steamboat Rock is in view and we reach the confluence. This spot, where two rivers come together, is a special place. Confluences hold powerful energy, as two separate rivers become one, the waters mixing, forming a new river.

Here, the Yampa’s olive brown color combines with the much clearer Green River. The Green is different because Flaming Gorge Dam, built upstream on the Green in 1964, stopped a lot of sediment from moving downstream. The dam has also changed the Green’s natural water flows. So, the wild Yampa is valuable to the health of the Green, delivering sediment and more natural flows to the lower stretch of the river and beyond.

We climb out of the rafts and hike up the sandstone to a viewpoint. Watch videos of Matt Rice, Colorado conservation director for American Rivers, describing the difference between the Green and the Yampa, and hear why he thinks Echo Park is a special place.

John Wesley Powell camped here in 1869 during his historic exploration of the Green and Colorado rivers.

Downstream from Echo Park we float down the Green through canyons of blocky dark red Uinta formation rock, capped with the thin pancake pink rock of the Lodore formation.

Against the dark red, it’s easy to spot the silvery wood of an old ladder, propped against the canyon wall. Surveyors left the ladder here in the 1950’s, studying sites for dams that would have drowned Echo Park and Dinosaur National Monument. The fight over these dams is one of the best known battles in river conservation.

I’ve been reading Kevin Fedarko’s new book The Emerald Mile, and he describes the victory won by the Sierra Club’s David Brower when the proposed Dinosaur dams were struck down – and the tradeoffs:

“For Brower and his colleagues, this victory marked a watershed moment in the politics of conservation. For the first time ever, a powerful coalition of federal bureaucrats and their allies had been bested by a band of “punks,” as one cabinet official had derisively dubbed the conservationists. But while all of this seemed to offer ample case for celebration, the victory had come at a steep price. At the center of the compromise to which Brower agreed was a dam that was slated to be built on the Colorado River fifteen miles upstream from the Grand Canyon… The dam’s reservoir would inundate a little-known river corridor called Glen Canyon, which was not part of any park or monument. Whatever wonders that obscure canyon might contain, it had never received federal protection of any kind… By agreeing to the compromise, Brower had, in effect, traded away something he had never seen on the assumption that it could not possibly match the value of what he was trying to save. This, as he was about to discover, was a terrible mistake.”

The old ladder stands as a reminder of how easy it is to lose something wild, and how important it is to protect special places before it’s too late.

Not many Americans are familiar with the Yampa, but we aim to change that. This river is not only a treasure of the Colorado Basin, it’s a national treasure as well.

Over the course of this trip we’ve had many good discussions around the campfire at night and in the rafts during the day. While we come from different organizations and agencies and have different goals and perspectives, I know we all agree that the wild Yampa is a unique and special place. This trip brought us together, and there is no doubt we’ll continue to work together to figure out the best strategy for ensuring the Yampa stays wild for generations to come.

Big thanks to Friends of the Yampa, George Wendt and OARS, Kent Vertrees and Matt Rice, our guides Bruce, Russell, Kate, Jules, Pat and John, and everybody who participated in this trip. It was a privilege being on the river with you!

National Geographic News Watch

Amy Kober of American Rivers

Original article